Customizing ASP.NET Core Part 06: Middlewares

Jürgen Gutsch - 08 October, 2018

Update 2021-02-01

This series is pretty much outdated!

As asked by a reader, I compiled the entire series into a book and updated the contents to the latest version of ASP.NET Core. This book is now ready to get ordered on Amazon:

Read here to learn more about the book

Wow, it is already the sixth part of this series. In this post I'm going to write about middlewares and how you can use them to customize your app a little more. I quickly go threw the basics about middlewares and than I'll write about some more specials things you can do with middlewares.

The series topics

- Customizing ASP.NET Core Part 01: Logging

- Customizing ASP.NET Core Part 02: Configuration

- Customizing ASP.NET Core Part 03: Dependency Injection

- Customizing ASP.NET Core Part 04: HTTPS

- Customizing ASP.NET Core Part 05: HostedServices

- Customizing ASP.NET Core Part 06: Middlewares - This article

- Customizing ASP.NET Core Part 07: OutputFormatter

- Customizing ASP.NET Core Part 08: ModelBinders

- Customizing ASP.NET Core Part 09: ActionFilter

- Customizing ASP.NET Core Part 10: TagHelpers

- Customizing ASP.NET Core Part 11: WebHostBuilder

- customizing ASP.NET Core Part 12: Hosting

About middlewares

The most of you already know what middlewares are, but some of you maybe don't. Even if you already use ASP.NET Core for a while, you don't really need to know details about middlewares, because they are mostly hidden behind nicely named extension methods like UseMvc(), UseAuthentication(), UseDeveloperExceptionPage() and so on. Every time you call a Use-method in the Startup.cs in the Configure method, you'll implicitly use at least one ore maybe more middlewares.

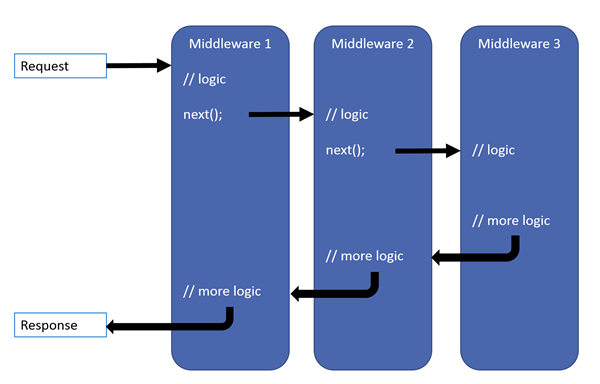

A middleware is a peace of code that handles the request pipeline. Imagine the request pipeline as huge tube where you can call something in and where an echo comes back. The middlewares are responsible for create this echo or to manipulate the sound, to enrich the information or to handle the source sound or to handle the echo.

Middlewares are executed in the order they are configured. The first configured middleware is the first that gets executed.

In an ASP.NET Core web, if the client requests an image or any other static file, the StaticFileMiddleware searches for that resource and return that resource if it finds one. If not this middleware does nothing except to call the next one. If there is no last middleware that handles the request pipeline, the request returns nothing. The MvcMiddleware also checks the requested resource, tries to map it to a configured route, executes the controller, created a view and returns a HTML or Web API result. If the MvcMiddleware doesn't find a matching controller, it anyway will return a result in this case it is a 404 Status result. It returns an echo in any case. This is why the MvcMiddleware is the last configured middleware.

(Image source: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/aspnet/core/fundamentals/middleware/?view=aspnetcore-2.1)

(Image source: https://docs.microsoft.com/en-us/aspnet/core/fundamentals/middleware/?view=aspnetcore-2.1)

An exception handling middleware usually is one of the first configured middleware, but it is not because it get's executed at first, but at last. The first configured middleware is also the last one if the echo comes back the tube. An exception handling middleware validates the result and displays a possible exception in a browser and client friendly way. This is where a runtime error gets an 500 Status.

You are able to see how the pipeline is executed if you create an empty ASP.NET Core application. I usually use the console and the .NET CLI tools:

dotnet new web -n MiddleWaresSample -o MiddleWaresSample

cd MiddleWaresSample

Open the Startup.cs with your favorite editor. It should be pretty empty compared to a regular ASP.NET Core application:

public class Startup

{

// This method gets called by the runtime. Use this method to add services to the container.

// For more information on how to configure your application, visit https://go.microsoft.com/fwlink/?LinkID=398940

public void ConfigureServices(IServiceCollection services)

{

}

// This method gets called by the runtime. Use this method to configure the HTTP request pipeline.

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app, IHostingEnvironment env)

{

if (env.IsDevelopment())

{

app.UseDeveloperExceptionPage();

}

app.Run(async (context) =>

{

await context.Response.WriteAsync("Hello World!");

});

}

}

There is the DeveloperExceptionPageMiddleware used and a special lambda middleware that only writes "Hello World!" to the response stream. The response stream is the echo I wrote about previously. This special middleware stops the pipeline and returns something as an echo. So it is the last one.

Leave this middleware and add the following lines right before the app.Run():

app.Use(async (context, next) =>

{

await context.Response.WriteAsync("===");

await next();

await context.Response.WriteAsync("===");

});

app.Use(async (context, next) =>

{

await context.Response.WriteAsync(">>>>>> ");

await next();

await context.Response.WriteAsync(" <<<<<<");

});

This two calls of app.Use() also creates two lambda middlewares, but this time the middlewares are calling the next ones. Each middleware knows the next one and calls it. Both middleware writing to the response stream before and after the next middleware is called. This should demonstrate how the pipeline works. Before the next middleware is called the actual request is handled and after the next middleware is called, the response (echo) is handled.

If you now run the application (using dotnet run) and open the displayed URL in the browser, you should see a plain text result like this:

===>>>>>> Hello World! <<<<<<===

Does this make sense to you? If yes, let's see how to use this concept to add some additional functionality to the request pipeline.

Writing a custom middleware

ASP.NET Core is based on middlewares. All the logic that gets executed during a request is somehow based on a middleware. So we are able to use this to add custom functionality to the web. We want to know the execution time of every request that goes through the request pipeline. I do this by creating and starting a Stopwatch before the next middleware is called and by stop measuring the execution time after the next middleware is called:

app.Use(async (context, next) =>

{

var s = new Stopwatch();

s.Start();

// execute the rest of the pipeline

await next();

s.Stop(); //stop measuring

var result = s.ElapsedMilliseconds;

// write out the milliseconds needed

await context.Response.WriteAsync($"Time needed: {result }");

});

After that I write out the elapsed milliseconds to the response stream.

If you write some more middlewares the Configure method in the Startup.cs get's pretty messy. This is why the most middlewares are written as separate classes. This could look like this:

public class StopwatchMiddleWare

{

private readonly RequestDelegate _next;

public StopwatchMiddleWare(RequestDelegate next)

{

_next = next;

}

public async Task Invoke(HttpContext context)

{

var s = new Stopwatch();

s.Start();

// execute the rest of the pipeline

await next();

s.Stop(); //stop measuring

var result = s.ElapsedMilliseconds;

// write out the milliseconds needed

await context.Response.WriteAsync($"Time needed: {result }");

}

}

This way we get the next middleware via the constructor and the current context in the Invoke() method.

Note: The Middleware is initialized on the start of the application and exists once during the application lifetime. The constructor gets called once. On the other hand the Invoke() method is called once per request.

To use this middleware, there is a generic UseMiddleware() method available you can use in the configure method:

app.UseMiddleware<StopwatchMiddleware>();

The more elegant way is to create an extensions method that encapsulates this call:

public static class StopwatchMiddlewareExtension

{

public static IApplicationBuilder UseStopwatch(this IApplicationBuilder app)

{

app.UseMiddleware<StopwatchMiddleware>();

return app;

}

}

Now can simply call it like this:

app.useStopwatch();

This is the way you can provide additional functionality to a ASP.NET Core web through the request pipeline. You are able to manipulate the request or even the response using middlewares.

The AuthenticationMiddleware for example tries to request user information from the request. If it doesn't find some it asked the client about it by sending a specific response back to the client. If it finds some, it adds the information to the request context and makes it available to the entire application this way.

What else can we do using middlewares?

Did you know that you can divert the request pipeline into two or more branches?

The next snippet shows how to create branches based on specific paths:

app.Map("/map1", app1 =>

{

// some more middlewares

app1.Run(async context =>

{

await context.Response.WriteAsync("Map Test 1");

});

});

app.Map("/map2", app2 =>

{

// some more middlewares

app2.Run(async context =>

{

await context.Response.WriteAsync("Map Test 2");

});

});

// some more middlewares

app.Run(async (context) =>

{

await context.Response.WriteAsync("Hello World!");

});

The path "/map1" is a specific branch that continues the request pipeline inside. The same with "/map2". Both maps have their own middleware configurations inside. All other not specified paths will follow the main branch.

There's also a MapWhen() method to branch the pipeline based on a condition instead of branch based on a path:

public void Configure(IApplicationBuilder app)

{

app.MapWhen(context => context.Request.Query.ContainsKey("branch"),

app1 =>

{

// some more middlewares

app1.Run(async context =>

{

await context.Response.WriteAsync("MapBranch Test");

});

});

// some more middlewares

app.Run(async context =>

{

await context.Response.WriteAsync("Hello from non-Map delegate. <p>");

});

}

You can create conditions based on configuration values or as shown here, based on properties of the request context. In this case a query string property is used. You can use HTTP headers, form properties or any other property of the request context.

You are also able to nest the maps to create child and grandchild branches of needed.

Map() or MapWhen() is used to provide a special API or resource based an a specific path or a specific condition. The ASP.NET Core HealthCheck API is done like this. It first uses MapWhen() to specify the port to use and then the Map() to set the path for the HealthCheck API, or it uses Map() only if no port is specified. At the end the HealthCheckMiddleware is used:

private static void UseHealthChecksCore(IApplicationBuilder app, PathString path, int? port, object[] args)

{

if (port == null)

{

app.Map(path, b => b.UseMiddleware<HealthCheckMiddleware>(args));

}

else

{

app.MapWhen(

c => c.Connection.LocalPort == port,

b0 => b0.Map(path, b1 => b1.UseMiddleware<HealthCheckMiddleware>(args)));

}

}

(See here on GitHib)

UPDATE 10/10/2018

After I published this post Hisham asked me a question on Twitter:

Another question that's middlewares related, I'm not sure why I never seen anyone using IMiddleware instead of writing InvokeAsync manually?!!

IMiddleware is new in ASP.NET Core 2.0 and actually I never knew that it exists before he tweeted about it. I'll definitely have a deeper look into IMiddleware and will write about it. Until that you should read Hishams really good post about it: Why you aren't using IMiddleware?

Conclusion

Most of the ASP.NET Core features are based on middlewares and we are able to extend ASP.NET Core by creating our own middlewares.

In the next to chapters I will have a look into different data types and how to handle them. I will create API outputs with any format and data type I want and except data of any type and format. Read the next part about Customizing ASP.NET Core Part 07: OutputFormatter